Tax regime for impatriate workers: A change intended to save money that will actually cost Belgium dearly, both financially and in terms of international competitiveness (Echo 18-1-2022)

Posted the 3 February 2022In 1983, Belgium introduced a special regime for expatriates via Circular CI. RH.624-325.294 dated 08.08.1983. This regime aimed to encourage multinationals to establish themselves in Belgium and bring in foreign executives. Essentially, it treated expatriate workers as non-residents for tax purposes and offered two main benefits: an expatriation allowance exempt from income tax and social security contributions of €11,250 (€29,750 for researchers) and an exemption from Belgian taxes on salaries for workdays spent abroad.

This benefit is particularly advantageous for executives who travel frequently. Additionally, when they are no longer tax residents in another country, their foreign earnings remain untaxed.

Currently, 20,000 workers benefit from this regime.

The new "special tax regime for impatriate taxpayers and researchers" takes effect on January 1, 2022, with the old regime being phased out after a two-year transition period.

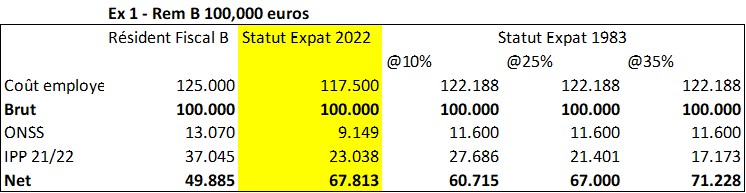

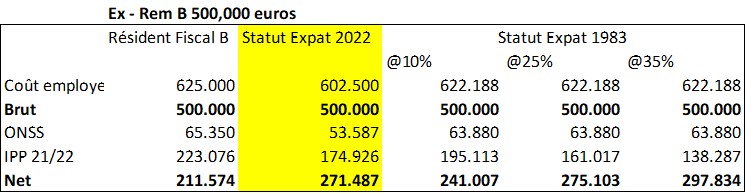

This new regime provides only for an expatriation allowance fixed at 30% of gross salary, capped at €90,000. Calculations show that the new regime results in a net outcome comparable to the old one for allowances of €11,250 and a travel percentage of 25%. On the surface, this seems reasonable.

However, the new regime is less favorable for very high earners (over €300,000 annually) and executives who travel extensively (over 30% of their workdays). Additionally, it is limited to five years (extendable to eight), whereas the old regime had no maximum duration for tax purposes (although social security applied a 15-year limit).

Calculations are for illustrative purposes only.

Among the justifications put forward, the only valid one is budgetary: to "reduce the fiscal revenue shortfall," estimated at €34 million. The others (statelessness, requests from lawyers and tax advisors, risks of disputes with the European Commission, etc.) are merely distractions.

A particularly concerning revelation in the preparatory works admits that, while the regime is popular and has attracted numerous investors, it is "difficult to assess the broader economic consequences of the old regime's elimination and the introduction of the new framework." What government enacts such a measure without evaluating the potential loss from companies like Swift or Mastercard relocating?

Moreover, this decision reflects a lack of comprehensive strategic thinking, driven solely by tax considerations. Replacing the travel percentage with a 30% expatriation allowance means that while previously exempted foreign travel salaries were subject to social security contributions, allowances are not. This creates a significant potential loss for social security, estimated in the tens or even hundreds of millions of euros.

The government risks undermining Belgium's international position without understanding the impact on its attractiveness, all to save €30 million—assuming the number of expats remains unchanged, which is uncertain. In reality, the measure is likely to result in a substantial loss of social security revenue. A legislative amendment will undoubtedly follow in the coming months to further complicate remuneration rules (e.g., treating the allowance as taxable income for social security purposes but not for fiscal purposes up to a certain limit). Yet another example of Belgium’s (mis)management in action.

L'Echo, January 18, 2022

Related articles

Is an employer allowed to mandate the use of artificial intelligence tools by employees ? (Trends, 17-07-2025)

Caution if a former colleague opposed to your employer asks you to testify in their favor